excerpts from A 1970s Essay Predicted Silicon Valley’s High-Minded Tyranny | WIRED

while this rhetoric of personal empowerment has been great for Silicon Valley, for the rest of the world it has produced a deeply painful reality: greater disparity in wealth and power, fewer tools for reversing these conditions, and a false sense that we are personally to blame for our own difficult circumstances.

The women’s liberation movement of the late 1960s was rebuilding the world in a consciously different way: no designated leaders and no rules on what you could say and when you could say it. Yet Freeman wondered if getting rid of rules and leaders was actually making feminism more open and fair.

After a hard think, she concluded that, if anything, the lack of structure made the situation worse: Elite women who went to the right schools and knew the right people held power and outsiders had no viable way of challenging them. She decided to write an essay summing up her thoughts. “As long as the structure of the group is informal, the rules of how decisions are made are known only to a few and awareness of power is limited to those who know the rules,” she wrote in the piece, published in Ms. magazine in 1973. “Those who do not know the rules and are not chosen for initiation must remain in confusion, or suffer from paranoid delusions that something is happening of which they are not quite aware.”

…

More than 40 years later, Freeman’s essay, “The Tyranny of Structurelessness,” continues to reverberate, especially in Silicon Valley, where it is deployed by a wide range of critics to disprove widely held beliefs about the internet as a force of personal empowerment, whether in work, leisure, or politics.

…

The reality, of course, is a bit different. Bitcoin is dominated by a small cadre of investors, and “mining” new coins is so expensive and electricity-draining that only large institutions can participate; Facebook’s advertising system is exploited by foreign governments and other malevolent political actors who have had free rein to spread disinformation and discord; and Google’s informal structure allows leaders to believe they can act in secret to dispense with credible accusations of harassment.

In Freeman’s unstinting language, this rhetoric of openness “becomes a smokescreen for the strong or the lucky to establish unquestioned hegemony over others.”

Because “Tyranny” explains how things work, as opposed to how people say things work, it has become a touchstone for social critics of all stripes. During the Occupy movement, Freeman’s essay was on the organizers’ minds when they sought to eliminate hierarchy without introducing a hidden hierarchy. … digital culture is where Freeman’s work has the most currency these days.

Benjamin Mako Hill, a fellow at Stanford’s Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, where he is studying how free software projects operate, said Freeman’s essay was “really an inspirational thing.” In many of the communities he researches, Hill said (refering to Jo Freeman’s essay), participants reject any hint of formal structures or authority only to discover that “10 years later, there really are a lot of leaders and structures.” Because the leaders and structures arrived informally, he said, they are much harder to uproot.

“Tyranny” was a healthy reminder that Silicon Valley’s rhetoric of openness and meritocracy doesn’t match the reality. “I’ve felt that paranoid delusion myself,” Taylor wrote in her book about the internet, The People’s Platform.

“How do you explain inequalities in a system where explicit discrimination doesn’t exist?

How do you make sense of homogeneity when there’s no sign on the door excluding different types of people?”

Freeman takes the long view about her argument, seeing it as part of a permanent push-pull between structure and structurelessness. There may be particular reasons why Silicon Valley leaders have an aversion to outside authority and rules, but mainly she thinks they embody the excessive enthusiasm of any group who gains a foothold in a new field—whether in oil exploration or railroads or the internet—and decides they are uniquely fit to hold that powerful position. In the early days of the internet, she says, “it was highly inventive, it was highly spontaneous, but we’re past that. As long as you reject the idea that any organization is bad you are never going to have the discussion about the best organization for whatever it is you are trying to do.”

And while this rhetoric of personal empowerment has been great for Silicon Valley, for the rest of the world it has produced a deeply painful reality: greater disparity in wealth and power, fewer tools for reversing these conditions, and a false sense that we are personally to blame for our own difficult circumstances. …

Excerpts from The Tyranny of Structurelessness by Jo Freeman

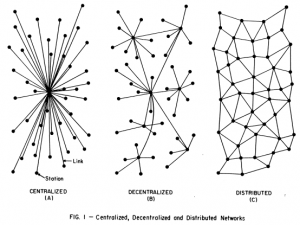

Formal and informal structures

Contrary to what we would like to believe, there is no such thing as a structureless group. Any group of people of whatever nature that comes together for any length of time for any purpose will inevitably structure itself in some fashion. The structure may be flexible; it may vary over time; it may evenly or unevenly distribute tasks, power and resources over the members of the group. But it will be formed regardless of the abilities, personalities, or intentions of the people involved. The very fact that we are individuals, with different talents, predispositions, and backgrounds makes this inevitable. Only if we refused to relate or interact on any basis whatsoever could we approximate structurelessness — and that is not the nature of a human group.

The nature of elitism

“Elitist” is probably the most abused word in the women’s liberation movement. It is used as frequently, and for the same reasons, as “pinko” was used in the fifties. It is rarely used correctly. Within the movement it commonly refers to individuals, though the personal characteristics and activities of those to whom it is directed may differ widely: An individual, as an individual can never be an elitist, because the only proper application of the term “elite” is to groups. Any individual, regardless of how well-known that person may be, can never be an elite.

Political impotence

Unstructured groups may be very effective in getting women to talk about their lives; they aren’t very good for getting things done. It is when people get tired of “just talking” and want to do something more that the groups flounder, unless they change the nature of their operation. Occasionally, the developed informal structure of the group coincides with an available need that the group can fill in such a way as to give the appearance that an Unstructured group “works.” That is, the group has fortuitously developed precisely the kind of structure best suited for engaging in a particular project.

There are almost inevitably four conditions found in such a group;

1) It is task oriented. Its function is very narrow and very specific, like putting on a conference or putting out a newspaper.

2) It is relatively small and homogeneous. Homogeneity is necessary to insure that participants have a “common language” for interaction.

3) There is a high degree of communication. Information must be passed on to everyone, opinions checked, work divided up, and participation assured in the relevant decisions. This is only possible if the group is small and people practically live together for the most crucial phases of the task.

Principles of democratic structuring

1) Delegation of specific authority to specific individuals for specific tasks by democratic procedures.

2) Requiring all those to whom authority has been delegated to be responsible to those who selected them.

3) Distribution of authority among as many people as is reasonably possible.

4) Rotation of tasks among individuals.

5) Allocation of tasks along rational criteria.

6) Diffusion of information to everyone as frequently as possible. Information is power. Access to information enhances one’s power.

7) Equal access to resources needed by the group. A member who maintains a monopoly over a needed resource (like a printing press owned by a husband, or a darkroom) can unduly influence the use of that resource. Skills and information are also resources.