…to draw the line between anticompetitive behavior, which is illegal under federal antitrust law, and hypercompetitive behavior, which is not.

Origen: Apple, Epic, and the App Store – Stratechery by Ben Thompson

What makes this distinction particularly challenging is that the question as to what is anticompetitive and what is simply good business changes as a business scales. … The specific case of Apple and the iPhone raises an additional angle: should the importance of the market in the question make a difference as well?

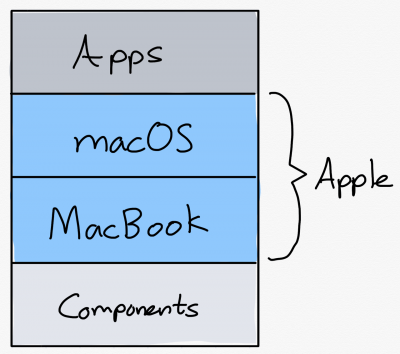

Apple integrates hardware made with industry-standard components and macOS, providing a platform for even more app developers.

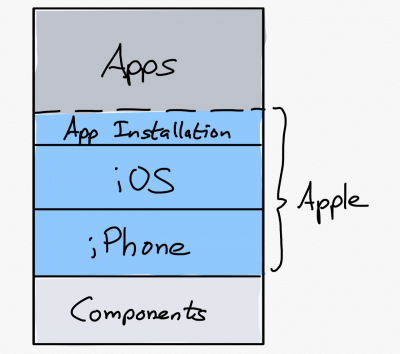

…iPhones have already been using Apple’s own chips for a decade; what has always made the iPhone different than the Mac, though, is the degree to which Apple has forward-integrated into the app ecosystem. What is critical to understand is that this integration proceeded in parts, and that those parts build on each other.

It is essential to note that this forward integration has had huge benefits for everyone involved. While Apple pretends like the Internet never existed as a distribution channel, the truth is it was a channel that wasn’t great for a lot of users: people were scared to install apps, convinced they would mess up their computers, get ripped off, or accidentally install a virus.

The App Store changed all of that: Apple effectively extended the trust it had earned with users over the years to all developers in the App Store. Users could install whatever they wanted, confident the app would not mess up their phone, rip them off, or be a virus. This by extension meant that the addressable market was far larger for app developers than the PC was, even though it would be several years before smartphones had a larger installed base than PCs.

From the beginning Apple kept 30% of every purchase; that was similar to the rate the company kept for iTunes purchases, and perhaps more pertinently, just barely covered credit card processing fees for a $0.99 app.

This gets at why this was another great deal for everyone involved: most users had already trusted Apple with their credit card information, and again, Apple was extending that trust to every developer in its App Store, making it far more likely that developers would earn money on their apps than if they had to drive downloads and purchases on their own. And once again, this circled back to Apple’s benefit, both in terms of the ecosystem broadly and, as the App Store reached scale (and added in-app purchasing), real profits.

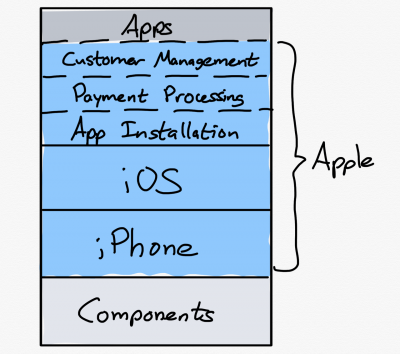

Users didn’t pay developers, they paid Apple, who paid developers. Users didn’t get receipts from developers, they got receipts from Apple, who kept their email address for themselves. This did have some user benefits, particularly in terms of ensuring their data was not sold to unscrupulous data brokers, but the benefit to developers was much less clear cut. There remains no means to offer refunds, for example, and for many years developers could not respond to negative reviews in the App Store.

What was most frustrating for developers, though, was that the lack of a customer relationship, in conjunction with the lack of functionality for upgrade pricing, made it difficult to build sustainable businesses in product spaces that did not have an obvious service component (which might require a subscription) or consumables (which could be bought with in-app purchases). The App Store was about transactions, not relationships, and Apple liked it that way…

There is a bit of a running joke in tech that the mainstream media believes that every tech company is ridiculously over-valued right up until the day that the exact same company is a juggernaut that is killing industries; in the case of Apple, the company’s strategy was doomed right up until it was illegal, or so it seems with the App Store.

In truth, though, while many of the issues surrounding the App Store are about Apple being a whole lot bigger than they were in 2008, the company has, particularly over the last few years, extended its control further and further away from the core integration that undergirds its business.

…

I have long believed that the Internet is going to fundamentally remake all aspects of society, including the economy, and that one area of immense promise is small-scale entrepreneurship. The App Store was, at least at the beginning, a wonderful example of this promise; as Jobs noted even the smallest developer could reach every iPhone on earth. Unfortunately, without even a whiff of competition, the App Store has now become a burden for most small developers, who instead of relying on the end-to-end functionality offered by, say, Stripe, have to support at least two payment solutions, the combined functionality of which is limited to the lowest common denominator, i.e. the App Store.

All that noted, what does remain valuable is Apple’s total control of the installation process.

Epic is attacking every level of the iPhone stack: the company doesn’t just want a direct relationship with customers, and it doesn’t just want to use its own payment processor; it is also demanding the right to run its own App Store.

My preferred outcome would see Apple maintaining its control of app installation. I treasure and depend on the openness of PCs and Macs, but I am also relieved that the iPhone is so dependable for those less technically savvy than me. What would be a far better outcome, at least from my perspective, would be Apple remembering that those same users that benefit from the iPhone being locked down should be the focus everywhere.

That means, for example, allowing purchases via webviews, particularly for products and experiences that do not have zero marginal costs. Sure, that could mean less App Store revenue in the short run, but Apple would be well-served having to build more and better products to win developers over.

While the most likely outcome is an Apple victory —the Supreme Court has been pretty consistent in holding that companies do not have a “duty to deal”— every decision the company makes that favors only itself, and not society generally, is an invitation to examine just how important the iPhone is to, well, everything.

Indeed, this is the most frustrating aspect of this debate: Apple consistently acts like a company peeved it is not getting its fair share, somehow ignoring the fact it is worth nearly $2 trillion precisely because the iPhone matters more than anything. This is not a console you play to entertain yourself, or even a PC for work: it is the foundation of modern life, which makes it all the more disappointing that Apple seems to care more about its short term bottom line than it does about the users and developers that used to share in its integration upside; if Apple doesn’t change course, hyperessential will at some point trump hypercompetitive.